Nate Soares reviews a dozen plans and proposals for making AI go well. He finds that almost none of them grapple with what he considers the core problem - capabilities will suddenly generalize way past training, but alignment won't.

Popular Comments

Recent Discussion

- Altruism is truly selfless, and it’s good.

- Altruism is truly selfless, and it’s bad.

- Altruism is enlightened self-interest, which is good.

- Altruism is disguised/corrupted/decadent self-interest, which is bad.

To illustrate further, though at the risk of oversimplifying…

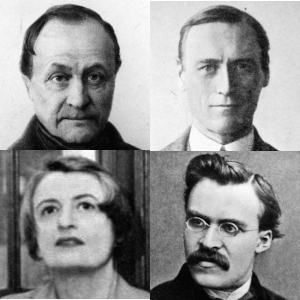

One exponent of option #1 would be Auguste Comte who thought that living for others was the foundation of true morality and of the best society.[1]

An exponent of option #2 would be Ayn Rand, who thought that altruism was indeed a doctrine of selflessness, but that this was the antithesis of true morality, and a threat to people.[2]

An exponent of option #3 would be Pierre Cérésole, who felt that altruism is what results when you refine your self-interest successfully and rid it of its mistakes.[3]

An exponent of option #4 would be Nietzsche, who thought altruism...

I don't think any one option is precise enough that it's correct on its own, so I will have to say "5" as well.

Here's my take:

- Altruism can be a result of both good and bad mental states.

- Helping others tends to be good for them, at least temporarily.

- Helping people can prevent them from helping themselves, and from growing.

- Helping something exist which wouldn't exist without your help is to get in the way of natural selection, which over time can result in many groups who are a net negative for society in that they require more than they provide. They might

Claim: memeticity in a scientific field is mostly determined, not by the most competent researchers in the field, but instead by roughly-median researchers. We’ll call this the “median researcher problem”.

Prototypical example: imagine a scientific field in which the large majority of practitioners have a very poor understanding of statistics, p-hacking, etc. Then lots of work in that field will be highly memetic despite trash statistics, blatant p-hacking, etc. Sure, the most competent people in the field may recognize the problems, but the median researchers don’t, and in aggregate it’s mostly the median researchers who spread the memes.

(Defending that claim isn’t really the main focus of this post, but a couple pieces of legible evidence which are weakly in favor:

- People did in fact try to sound the alarm about poor

I don't think statistics incompetence is the One Main Thing, it's just an example which I expect to be relatively obvious and legible to readers here.

Saturday of Week 47 of 2024

Location:

Meeting room 5, Bellevue Library

1111 110th Ave NE, Bellevue, WA 98004'

Google Maps: https://g.co/kgs/ASXz22S

4hr Free Parking available in underground garage

Contact: cedar.ren@gmail.com

If you can't find us: please repeatedly call 7572794582

Bring boardgames

Bring questions

Might do lightning talks

Thank you for the clarification. Do you have a process or a methodology for when you try and solve this kind of "nobody knows" problems? Or is it one of those things where the very nature of these problems being so novel means that there is no broad method that can be applied?

A lot of threat models describing how AIs might escape our control (e.g. self-exfiltration, hacking the datacenter) start out with AIs that are acting as agents working autonomously on research tasks (especially AI R&D) in a datacenter controlled by the AI company. So I think it’s important to have a clear picture of how this kind of AI agent could work, and how it might be secured. I often talk to people who seem to have a somewhat confused picture of how this kind of agent setup would work that causes them to conflate some different versions of the threat model, and to miss some important points about which aspects of the system are easy or hard to defend.

So in this post, I’ll present a simple system architecture...

I've built very basic agents where (if I'm understanding correctly) my laptop is the Scaffold Server and there is no separate Execution Server; the agent executes Python code and bash commands locally. You mention that it seems bizarre to not set up a separate Execution Server (at least for more sophisticated agents) because the agent can break things on the Scaffold Server. But I'm inclined to think there may also be advantages to this for capabilities: namely, an agent can discover while performing a task that it would benefit from having tools that it d...

Summary

Four months after my post 'LLM Generality is a Timeline Crux', new research on o1-preview should update us significantly toward LLMs being capable of general reasoning, and hence of scaling straight to AGI, and shorten our timeline estimates.

Summary of previous post

In June of 2024, I wrote a post, 'LLM Generality is a Timeline Crux', in which I argue that

- LLMs seem on their face to be improving rapidly at reasoning.

- But there are some interesting exceptions where they still fail much more badly than one would expect given the rest of their capabilities, having to do with general reasoning. Some argue based on these exceptions that much of their apparent reasoning capability is much shallower than it appears, and that we're being fooled by having trouble internalizing just how

I like trying to define general reasoning; I also don't have a good definition. I think it's tricky.The ability to do deduction, induction, and abduction.

- The ability to do deduction, induction, and abduction.

I think you've got to define how well it does each of these. As you noted on that very difficult math benchmark comment, saying they can do general reasoning doesn't mean doing it infinitely well.

...

- The ability to do those in a careful, step by step way, with almost no errors (other than the errors that are inherent to induction and abduction on lim

If it’s worth saying, but not worth its own post, here's a place to put it.

If you are new to LessWrong, here's the place to introduce yourself. Personal stories, anecdotes, or just general comments on how you found us and what you hope to get from the site and community are invited. This is also the place to discuss feature requests and other ideas you have for the site, if you don't want to write a full top-level post.

If you're new to the community, you can start reading the Highlights from the Sequences, a collection of posts about the core ideas of LessWrong.

If you want to explore the community more, I recommend reading the Library, checking recent Curated posts, seeing if there are any meetups in your area, and checking out the Getting Started section of the LessWrong FAQ. If you want to orient to the content on the site, you can also check out the Concepts section.

The Open Thread tag is here. The Open Thread sequence is here.

When rereading [0 and 1 Are Not Probabilities], I thought: can we ever specify our amount of information in infinite domains, perhaps with something resembling hyperreals?

- An uniformly random rational number from is taken. There's an infinite number of options meaning that prior probabilities are all zero (), so we need infinite amount of evidence to single out any number.

(It's worth noting that we have codes that can encode any specific rational number with a finite word - for instance, first apply bijection of rationals to nat

Epistemic status: splitting hairs. Originally published as a shortform; thanks @Arjun Panickssery for telling me to publish this as a full post.

There’s been a lot of recent work on memory. This is great, but popular communication of that progress consistently mixes up active recall and spaced repetition. That consistently bugged me — hence this piece.

If you already have a good understanding of active recall and spaced repetition, skim sections I and II, then skip to section III.

Note: this piece doesn’t meticulously cite sources, and will probably be slightly out of date in a few years. I link to some great posts that have far more technical substance at the end, if you’re interested in learning more & actually reading the literature.

I. Active Recall

When you want to learn...

hmm, that's fair — i guess there's another, finer distinction here between "active recall" and chaining the mental motion of recalling of something to some triggering mental motion. i usually think of "active recall" as the process of:

- mental-state-1

- ~stuff going on in your brain~

- mental-state-2

over time, you build up an association between mental-state-1 and mental-state-2. doing this with active recall looks like being shown something that automatically triggers mental-state-1, then being forced to actively recall mental-state-2.

with names/faces, i think th...

Note: thank you Mark Budde, cofounder and CEO of Plasmidsaurus, and Maria Konovalova, a growth/marketing/talented-person at Plasmidsaurus, for talking to me for this article! Also thank you to Eryney Marrogi, who helped answer some of my dumb questions about plasmids.

Introduction

Here’s some important context for this essay: it really, really sucks to start a company in biology.

Despite billions in funding, the brightest minds the world has to offer, and clear market need, creating an enduring company here feels almost impossible. Some of this has to do with the difficulties of engaging with the world of atoms, some of it has to do with the modern state of enormously expensive clinical trials, and some of it still can be blamed on something else. To some degree, this is an unavoidable...

Yeah I can see that; I guess what I was trying to get across was that Plasimidsaurus did do a lot of cold reachout at the start (and, when they did do it, it was high-effort, thoughtful reachouts that took into account the labs needs), but largely stopped afterwords.